The Filthy Ground Upon Which We Walk: Subverting the Space of The Art Fair in Contemporary Cape Town

by Thuli Gamedze

The flooring of The Cape Town Art Fair at the V&A Waterfront (left), and That Art Fair, at a parking lot on Cecil Road, Salt River (right

That Art Fair created a space for artists that is generally lost in an art fair setup. While work was being sold quite well, the exchange was not only monetary- conversation and interest acted as feasible assets through which to navigate the space, and I would argue that these assets are the ones that prove more valuable to artists who are invariably trying to ‘make shit happen’.

After having wandered quietly through the Cape Town Art Fair amongst clean frames, perfectly mounted light jet prints, and flawlessly preserved South African modernist sculpture, what had struck me was the event’s incredible un-immersiveness. In this sense, I refer not just to the work but to the energy of the space, which is forcibly directed towards capital, and as such, ends up objectifying all those involved in the processes of artistic production and curatorial strategy.

In other words, I felt left out. However, (and without feeling too sorry for myself) having been quite used to this feeling in Cape Town, I was able to isolate and recognize the resoundingly clear commercial purpose of the art fair. In accepting the cold (and boring) parameters of the space, I think it is important to reflect on how ‘the art fair’, as an imported symbolic climax of absolute artistic and cultural progressiveness, attempts to situate itself within contemporary Cape Town, as opposed to, say, Basel, Switzerland.

There already exist innumerable tensions within urban South Africa that arise from the apartheid state that continues to perpetuate itself here. Within this framework, we can understand art fairs here as quite violent situations, which expose the crassness of the extreme capitalist Cape Town fine art economy. This economy is owned by a particular kind of whiteness, whose violence is its increasing appropriation of black Africanness as a contemporary art tool for capital, presented as some form of African cosmopolitan/ diasporic/ globalised ’inclusion’.

The question at hand is- while blackness does exist in abundance within the Cape Town art market, on what conditions is this inclusion based, and can we problematise the entire notion of who it is that acts as the inclusionary agent? In effect, the power dynamic plays out between white ownership, and black artists and movers within the art community. And so, in South Africa, I think it is worthwhile to note that beyond the problems of capitalist exchange, there exists a parallel negotiation where race, as well as sex and gender- where personhood- becomes trapped in this dangerous game of commodification.

‘That Art Fair’ as Healthy Subversion

Works as part of ongoing series by Swiss-Guinean artist Namsa Leuba, forming part of a larger body of work, entitled ‘Ethnomodern’, in association with Pro-Helvetica and the Swiss Arts Council

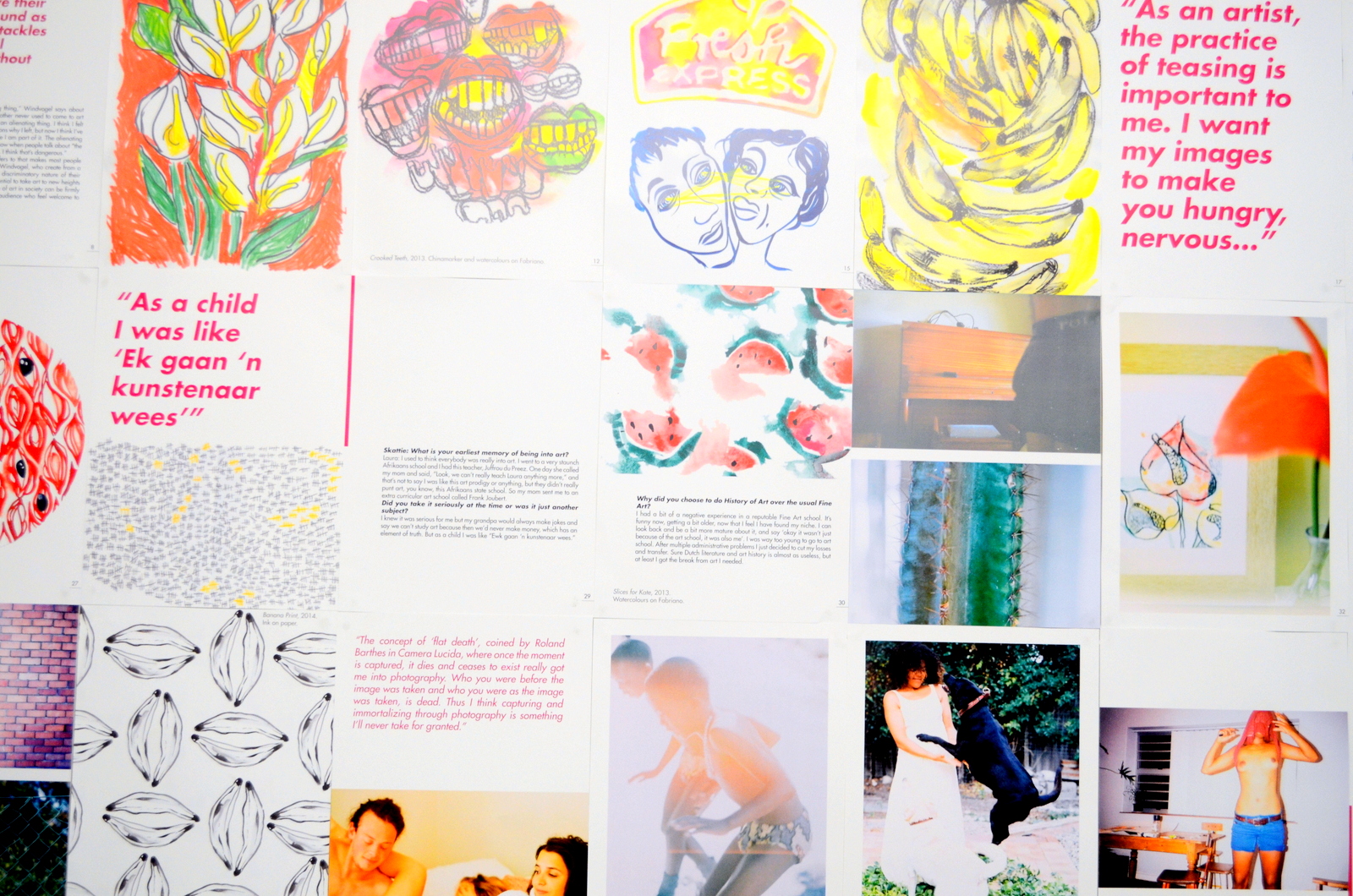

‘Skattie’ at That Art Fair: ‘Skattie Celebrates Laura Vindvogel’ (left), and sculptural work by Unathi Mkonto (right), an artist also recently featured in a ‘Skattie Celebrates’ publication

It seems apt therefore that That Art Fair, organized by Art South Africa, went about things very differently. In order to unpack the presented problems, we might look at this event as an artistic intervention that plays with the notion of exchange in South African art markets. If we think of it as such, there is a lot to be pulled from both situations.

I found That Art Fair very refreshing, and this portal into friendly exchange between artists, writers and organisers is something that is rare to observe in the unloving Mother City, and reads almost as a subversion of both the stiff cleanliness of the Art Fair, and the self-conscious ‘cool’ of the young Cape Town art crowd. Perhaps this can all be explained by the fact that at That Art Fair, black artists were exhibiting, and were present in person- not as trophies to white liberal collectors with old money.

Namsa Leuba’s work completely blew my mind in this regard, tacitly owning the fact that, even after much of this discourse has taken place, a black person photographing black people well still remains a revolutionary act within contemporary South Africa. Sadly (but LOL), we must often continue to ask in other Cape Town gallery setups- where are all the black people, except for in the white man’s photographs?

A relatively new Skattie project seemed to further these ideas of black ownership. Skattie Celebrates is a publication that displays the work of young artists, providing textual and interview accompaniment to the work, and dedicating an entire issue to give space to new talent. Though without overt references to race, and the all its associated nesses, their publication takes the position of creating new norms, and new spaces in which the black artist, editor, or writer- the black agent- is not ‘othered’. Within Skattie, it seems that this black-centric position is taken for granted with the same force that whiteness is in most spaces. Amongst many other projects being run by young artists of colour, both Leuba and Skattie magazine seemed to reflect a commitment to reconfiguring how we, as young people of colour, might engage with the South Africa of now, illustrating the possibility of productive space creation outside of the often destructive mainstream fine art market.

I can’t help but question the use of a space that is by nature, forcibly non-self-reflexive. I’m not trying to be inflammatory, and nor am I saying this as a result of being particularly bored as I walked around the Cape Town Art Fair- but I have to admit that the intervention that grabbed me the most particularly was, as far as I know, unplanned. As a result of their impracticality, a number of the hotshot galleries in the main marquee had ripped up the grey carpet squares from the ground, exposing the grubby wooden floors beneath.

In the disturbingly clean and expensive V&A Waterfront, this hint at some truth, some indication of the filthy foundation that the exhibited wealth was built upon, really resonated with me. I thought about it again at That Art Fair, which was held inside a parking lot that was under construction. There was no bullshit there, no pretence at creating a climatic moment, or a haven of culture, frozen in archival ink and mounted behind glass; there was no guise of resolvedness- there was just an awareness of being at a junction, and understanding that soon we’d be on our way to the next stop. And soon again, the next.

So perhaps, if there’s something we need more of in the Cape Town art scene, it’s simply the acceptance that we can never stay here long, or here, or there. We need to move, we need to hustle, because while we’re all practicing, writing, buying, selling, and speaking, we’re all balanced, and trying to build upon the filthiest and most rotten foundations.

Onward.

- Thuli Gamedze

Read more about Skattie Celebrates’ beginnings at www.artsouthafrica.com/220-news-articles-2013/2232-skattie-celebrates-launching-in-cape-town.html

Check out Namsa Leuba’s work at www.namsaleuba.com